Sustainable Innovation

The Wild sustainability and social innovation strategy

Introduction

Our sustainable innovation strategy is the foundation of Wild.

Outlined here is the science, philosophy and arguments guiding our business model.

Definitions

Social innovation is the process of developing and deploying effective solutions to challenging and often systemic social and environmental issues in support of social progress.

Stanford Graduate School of Business

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

UN World Commission on Environment and Development

Why this approach

When we in 2015 started coffee farming in Uganda, we quickly discovered who the coffee industry benefits, and who it doesn’t. We didn’t like what we found.

Honestly, it was shocking to realise the small share of the value of the coffee that remains where the coffee is grown, while almost all profits are made – and kept – in the richest countries on Earth.

All the while, the coffee producing countries remain poor. And the coffee farmers keep struggling to make ends meet.

There had to be a better way.

The problem can be divided into three parts:

1.

What the farmer is paid for their coffee is too low

2.

All the middlemen between the farmer and the end consumer, all keeping their share of the profits

3.

The value addition is done far away from where the coffee is grown

So we started looking for a better way

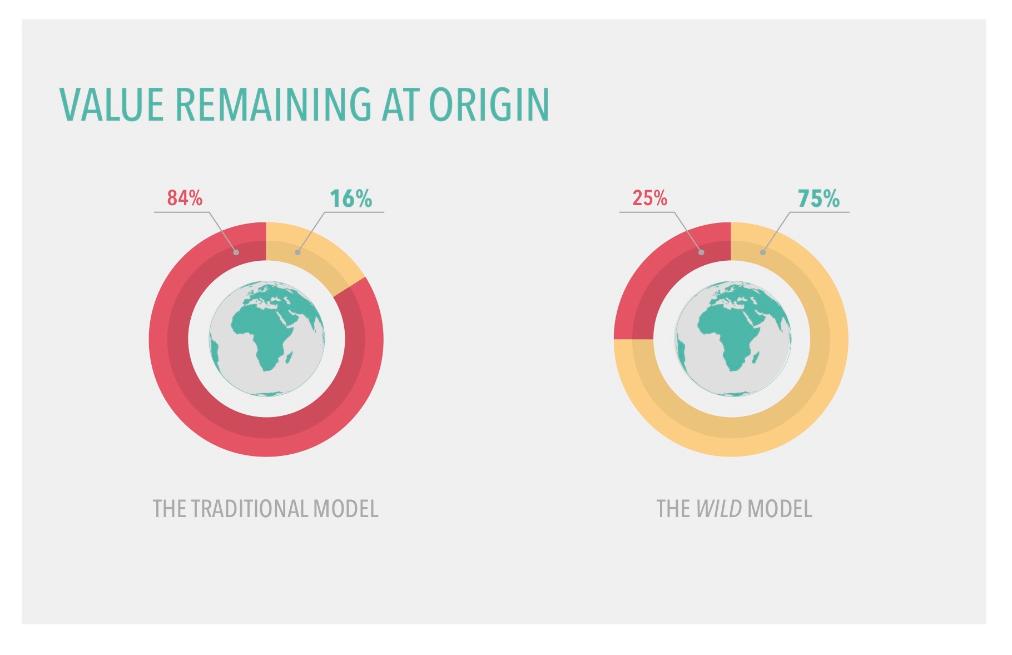

If we can eliminate the middlemen, we can pay the farmer better.

And if we can do everything here at origin, the impact for the local economy would be tremendous.

We soon realised there is only one solution: To turn the coffee industry on its head, and make sure the value of coffee remains at origin.

The potential is huge. This is why Wild is on a mission to change the coffee industry.

Our goals

1

Show the world a better coffee industry is possible

2

Offer the coffee farmers a better price for their coffee

3

Create jobs that utilise the vastly unrealised talent in Africa

4

Work with the farmers to target our common environmental challenges

5

Provide climate positive coffee

Goal 1:

Show the world a better coffee industry is possible

Coffee is enjoyed by billions all over the world every day. More than 2 billion cups are consumed daily. It fuels social connections, boosts productivity2, improves health3, and offers coffee lovers their daily dose of pure bliss.

It also generates enormous amounts of revenue for the coffee industry.

Unfortunately, only a small share of this revenue finds its way back to the coffee producing countries.

The reason for this is simple: the coffee growing countries export their coffee as a raw material, and the value addition is being done in the coffee consuming countries.

This business model has been the norm since colonial times:

4

Export the raw material through a long chain of middlemen, and do the value addition in the developed countries.

The higher up the value chain, the higher the share of the revenue and the profits.

When you buy a bag of coffee from either the supermarket or your favourite local specialty coffee roaster only about 16% of the money you pay goes back to the country where the coffee was grown.

84% remains in the consuming country.5

For a very long time, the "colonial model" has been the only option.

Coffee grows too far away from the consumers. Green coffee can be transported and stored for months without seriously impacting the quality, while roasted coffee has to reach the consumer in a shorter time.

Also, it used to be easier to run a coffee company from the US or Europe when it comes to everything from the logistics and distribution to management and marketing.

But not any more.

The time has finally come to throw the colonial model in the dustbin.

Being based at source comes with some amazing advantages

Uganda, The Pearl of Africa, is the perfect location for a coffee company: East Africa is the birthplace of coffee and we are surrounded by some of the best coffee producing nations in the world; from Ethiopia to Burundi, DR Congo to Kenya, making sourcing amazing coffee and connecting directly with the farmers so much easier.

Additionally, as Uganda is one of the least developed countries in the World, every hire and every investment have a direct impact where it's needed the most.

This is nothing less than a win-win model.

Goal 2:

Offer the farmers a better price for their coffee

“A sustainable coffee farmer will meet long term environmental and social goals, and will at the same time be able to compete effectively with other market participants and achieve prices that cover his production costs and allow him to earn an acceptable profit margin." [ 6]

Being a coffee farmer has never been easy. In East Africa, most of them are small scale farmers, and they are living in some of the least developed countries in the world.

Lately, coffee prices have been at the lowest levels for years. Basically, what the farmer receives is below the cost of production. [7]

Unfortunately, this is not unusual. Low cycles like this happen regularly.

Coffee farmers face many challenges. Here in East Africa, most of the coffee farms are small scale, giving the farms limited output. The regions producing the best quality are usually steep and hilly, making it impossible to use modern tools used by large scale plantations in other parts of the world. The roads are bad, making access to market and inputs more costly. Etc.

In our experience some steps can be made which have the potential to improve the farmer’s life:

- Higher prices*. We have a policy of paying a premium 100% above the five year lowest market price**. We are able to do this because we have eliminated the middlemen, selling directly to the end consumer, and because we deal in the specialty coffee market, where margins are higher.

- Help farmers improve their yield. Besides higher prices, this is the second factor that directly influences the farmers income. In East Africa, where yield is low, there is a big potential for improving yield.8

- Encourage coffee drinkers to shift from commodity coffee to specialty coffee. Not only is the taste so much better, specialty coffee usually pays the farmers better.

* Coffee is basically traded on two separate markets. The largest by far is the commodity market, where big lots are traded on the New York Coffee Exchange. This market determines the C-price. In addition to the commodity market is the specialty coffee market, where prices can be substantially higher. This is a smaller niche of the market, but fortunately growing as more and more coffee consumers are starting to appreciate higher quality beans. Unfortunately, far from all farmers are able to sell their coffee at specialty prices, even if their coffee is of very good quality. If they can not find a specialty buyer, they have to sell to commodity buyers.

** This price floor act as an insurance against the lows of the ever fluctuating coffee prices. As we primarily buy premium beans of specialty grade, we usually pay more than this anyway. Every farmer's base price is different, based on the actual farm gate price in their area.

Are you Fairtrade certified?

We get this question a lot. We are always glad to be asked. It shows that people care about the farmers. It shows they want a fair world with fair business practices. So do we. Many of our colleagues in the coffee industry are offering Fairtrade coffee. Should we do the same?

Studies on the efficiency of Fairtrade programmes have carried mixed results. A study of Nicaraguan coffee farmers discovered a positive correlation between participating in the Fairtrade scheme and higher financial returns. Simultaneously, impressions of higher stability in property possession were recorded. Yet, due to overall worsening conditions within the coffee market, on an overall level the lives of the farmers became more difficult. Fairtrade could only perform damage limitation. Thus the study concludes that Fairtrade must constantly evolve to maintain itself along general market developments.

A similar take is provided in another study [9]. While examining the household income of Fairtrade coffee farmers in seven different countries, they found that incomes strongly depend on aspects not affected by Fairtrade such as cost and volume of production. Therefore, in countries where such factors made conditions less favourable (e.g. Kenya) coffee production was not cost effective vis-à-vis countries with more favorable surrounding conditions (e.g. Vietnam). Externalities such as Kenyan farmers losing money by engaging in the coffee economy thus emerged. Hence, Fairtrade does not reach its objective of providing a sustainable income for every farmer. [10]

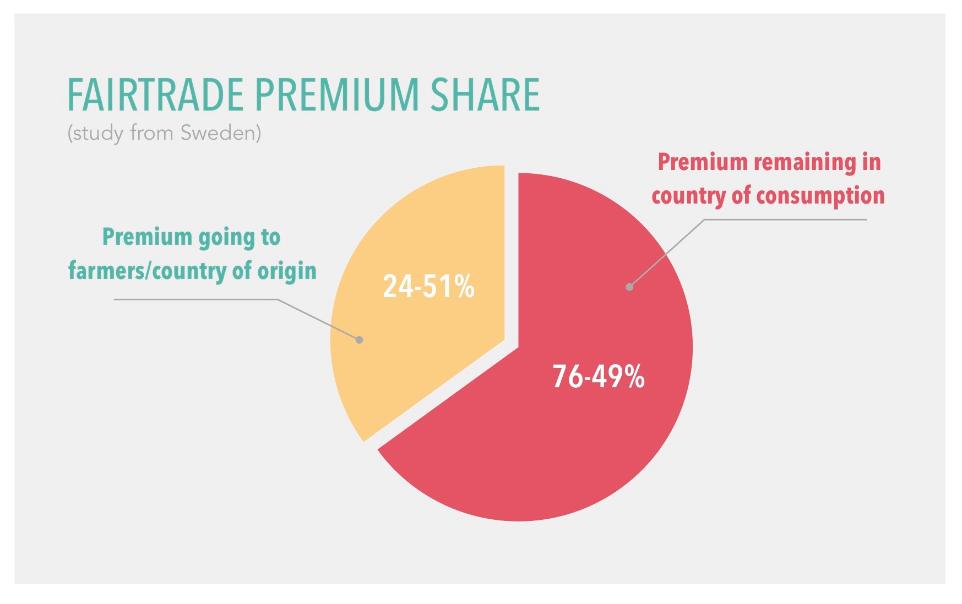

The premium the Fairtrade farmers receive is lower than many would probably expect. Research [11] commissioned by Fairtrade has shown that coffee farmers receive a price 8-26% higher than minimum prices “during periods of low prices”.

The globally influential NGO Oxfam likewise critiques Fairtrade’s patch-work account in its aspiration to create a truly fair trading system . In a 2002 paper called “Mugged, Poverty in your Coffee Cup”, Oxfam states that due to potentially higher incomes, farmers stay in coffee production instead of diversifying their income possibilities. Thus, an oversupply of coffee is created, which leads to a reduction of global market prices. However, Oxfam acknowledges that Fairtrade minimum prices can act as a safety net for farmers. This is especially the case in countries where the state can not provide adequate assistance in case of a price collapse. [12]

For further general discussion on Fairtrade effects on the livelihoods of coffee farmers see Nelson and Pound (2009) and for further local (Ugandan) analysis see Chiputwa et al. (2015).

In Sweden Durevall (2017) studied the allocation of the premium consumers pay for Fairtrade coffee. He found that roasters and retailers in Europe received up to 70% of the premium and thus benefited the most from the higher price. [13] This is particularly controversial as consumers likely purchase Fairtrade coffee to support poor farmers. [14] The argument that being a Fairtrade certified company is more beneficial for European and American companies compared to the coffee farmers is also reflected in a paper by Jaffee (2012). She argues that Fairtrade standards are weakened by powerful firms so they can also enjoy the positive brand image that comes with the certification, while limiting the beneficial effects for the farmers15.

Based on the available knowledge, we have chosen not to pursue Fairtrade certification, the main reasons being:

- The premium the farmers receive is too low. We know we can do better by buying directly from the farmer.

- Becoming Fairtrade certified is costly and time consuming. We believe our resources can be spent better.

- The ethical questions relating to the promises made and the realities of the system:

We find serious ethical concerns with a certificate given to companies and brands in the richest countries, who after giving a small share to the farmers, keep the bulk of revenue and profits in the developed world, where the companies are based, their staff works, and their taxes are paid. In other words, Fairtrade allows companies that operate under what we call the colonial model to put their seal of approval on their coffee bags, allowing a system where the poor stay poor while the rich get richer, to continue. Honestly, how is this fair trade?

We appreciate the intentions behind Fairtrade, and we understand why coffee brands choose to go with this solution. When you are based in Europe or the US, far from where the coffee is grown, it’s frankly limited what you can do. So you get Fairtrade certified, and everyone is happy. Problem solved, right?

No. The problems are not solved. To create a sustainable coffee industry for the future, benefiting everyone from the farmer to the barista, we need far more fundamental changes.

Goal 3:

Create jobs that utilise the vastly unrealised talent in Africa

Uganda has one of the youngest and fastest growing populations in the world. The population is expected to almost triple from 36.4 million (2014) to 102 million in 2050 [16]. The median age in Uganda is only 15.9 years, compared to 45.9 for Germany.

The demographic outlook poses some huge challenges. But also tremendous opportunities. This young population is a fantastic resource, just waiting to be utilised.

However, the current business environment here in Uganda is far from ready to provide job opportunities for Uganda’s ambitious and talented professionals. As a result, Ugandans cannot fulfill their true potential, having to scrape by on short term jobs in the informal sector. Jonah, a developer hired by Wild for a few weeks, says:

“We live in constant uncertainty, living day by day looking for short term jobs, never knowing if we can eat today. This is especially stressful for me as I have a family to feed.”

According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics 92% of the youth, aged 15 – 29, work in the informal sector. Needless to say, Uganda needs to create millions of jobs in the coming years. Where could they be generated?

How about in the coffee industry? Coffee is one of Uganda’s most important exports, but basically all coffee is exported as a raw material: unroasted, green beans.

The National Union of Coffee Agribusiness and Farm Enterprises (NUCAFE) has estimated [17] that if Uganda could export roasted coffee instead of solely green beans, the value of coffee exports could more than quadruple.

This is where the potential to fundamentally change the coffee Industry is found.

By doing the entire value chain at origin, export income increases substantially, while many new jobs will be created. From roasting and packaging, logistics and sales, IT, marketing, accounting and development of new sustainable business solutions, all can be done here at the birthplace of coffee.

There are few places where jobs like these are more needed.

Goal 4:

Work with the farmers to target our environmental challenges

The road to a sustainable coffee industry starts at the farm. Like with every agricultural product, coffee, in order to be sustainable, has to be grown with the least amount of impact on our environment.

But if the farmers can’t make a living from their coffee, we will have no coffee industry in the future.

These two concerns can not be separated.

“New threats brought on by climate change, conflict and food insecurity, mean even more work is needed to bring people out of poverty.” (UNDP SDG1: 2019)

In our opinion, a key metric to a more sustainable coffee industry is yield. East African coffee farmers have a huge potential in improving their yield.

If the yield is low, the farmer needs to use more land to increase her income. Using more land for farming means less land for forests and other ecosystems. As the global population grows to 10 billion, we can not use more land. On the contrary, we have to use less. The yield needs to increase for the sake of both the farmers and the planet.

Can organic coffee farming solve these challenges?

We have our own coffee farm; GLADfarm, where we have been growing coffee since 2015. Having our own coffee farm where we can experiment and do our own research is invaluable. GLADfarm is a model farm, pioneering better farming practices, and transferring this knowledge to farmers near and far. We have considered organic farming, not least because many customers ask for it. But available research shows mixed results when it comes to the benefits of organic farming. When comparing various academic papers on the organic coffee industry we found that H. A. M Van der Vossen (2005), A critical analysis of the agronomic and economic sustainability of organic coffee production, resembles our own empirical evidence quite well.

“There appears to be considerable injustice between the extreme preconditions demanded for ‘organics’ by the largely urban consumer of the industrialized world and the modest rewards received by the organic coffee growers for their strenuous efforts.” 18

We would love to be 100% organic, but we face some challenges reaching that goal. One of them is fighting pests and diseases attacking the coffee. Another is making sure the coffee trees get enough nutrients to provide maximum yield.

Says our farm manager at GLADfarm, Mark Norman Lumago: “There is no evidence of higher yields. Simultaneously, there is a risk of losing the coffee garden to pest or disease attacks. To counterbalance these factors farmers would need to use more land. This translates into a potential of cutting down more forests which would not rhyme with the sustainability program we are building.”

One of the outgrowers we are working with at GLADfarm; Alex Wasswa told us about the 500 coffee trees he has planted. He can either use 250 g of conventional fertilizer per plant, or one wheelbarrow (7 kg) of manure per plant. The manure is not only hard to find, it also needs to be transported and then applied, manually. A huge undertaking for a small scale farmer with few aids at his disposal.

“To sustain economically viable yield levels large additional amounts of composted organic matter will have to come from external sources to meet nutrient requirements. Most smallholders will be unable to acquire such quantities and have to face declining yields 19.”

There are lots of great practices from organic farming we gladly recommend implementing. But the foundation of our advice is Good Agricultural Practices (GAP); the best practices, to the best of our knowledge, for each farmer’s unique needs.

“It is concluded that the concept of organic farming in its strict sense, when applied to coffee, is not sustainable and also not serving the interests of the producer and consumer as much as the proponents would like us to believe. On the other hand, agronomically and economically sustainable coffee production is feasible by applying best practices of crop production and post-harvest processing.” (Van der Vossen 2005: 449).

In Norway, the home country of the founders of GLADfarm and Wild, we have this saying which is a bit tricky to translate into English, but it means something like “sound farmer’s wisdom”. It summarizes quite well how we think about farming: Use our best wisdom to create healthy farms and a healthy Earth.

Goal 5:

Provide climate positive coffee

Few challenges facing humanity are as grave and huge as the climate crisis. If we can not limit the rise of global warming, large areas of the earth may become uninhabitable. More than half of the coffee areas may become unsuitable for coffee growing. [20]

And more than 60% of the 124 known wild coffee species are at risk of extinction. [21]

Uganda’s population growth rate of 3.5% is putting a lot of pressure on natural resources. This is one of the main reasons why Uganda’s forest cover has been reduced from 24% in the 1990s to 8% in 2018 says the Ugandan ministry of Environment. Every year, 100.000 hectares of forest is lost in Uganda. [22]

We have no choice. We have to develop a sustainable world. And we have to start reversing the damage already done, by removing carbon from the atmosphere.

We want to contribute to this. Please allow us to present: The Wild Forest.

This is one of the projects we are most passionate about. By planting trees and re-wilding Uganda, we want to contribute to restoring Uganda’s lost forest cover, while offsetting the carbon footprint of our operations.

First of all, we want to work with our coffee farmers to plant more trees on their farms – when possible. Many farmers already use trees for shade, which is beneficial for the coffee. We do this on our coffee farm as well: Large parts of the farm is almost like a wild forest, with huge indigenous trees where a multitude of birds as well as monkeys thrive. We can truly say we have forest grown coffee. We want to encourage all farmers to adopt this practice.

The benefits of shade trees are many: they help control erosion on steeper grounds, shade trees suppress weeds, help with organic matter from litter and pruning, the quality of the cherries from shaded areas is better and the yield higher, there is less leaf rust, and it helps break the wind and heavy rainfall.

At the farm we still have large areas where we want to plant more shade trees. The planted trees will absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, allowing us to offset our carbon footprint from our coffee – all the way to the customer’s coffee cup.

As Wild grows, the land available for tree planting at GLADfarm will not be enough. We will then acquire additional land where the native forests have been cut down, and start re-planting native trees to bring the forests back. Re-generating lost rain-forest has a high potential for carbon capture.

In these forests we also want to plant some of the wild coffee species now threatened due to climate change and habitat loss.

We have to start re-wilding Uganda.

Our goal: to one day have a huge, amazing, truly Wild Forest, full of birds, animals, and all types of native trees and other flora. And of course, wild coffee!

References

1. NUCAFE in S. Mbowa, F. Nakazi, and J. Nkandu (2017): Looming Long-term Economic Effect of Climate Change on Uganda’s Coffee Industry, issue No. 96, Economic Policy Research Centre Kampala.

3. https://www.health.harvard.edu/press_releases/coffee_health_risk

4. Topik 2004, UN 2018: 7

5. Borrella et al. 2015: 41

6. http://www.ico.org/documents/cy2014-15/icc-114-5-r1e-overview-coffee-sector-africa.pdf

7. https://www.perfectdailygrind.com/2018/07/this-is-how-much-it-costs-to-produce-coffee-across-latin-america/

8. https://www.globalcoffeeplatform.org/assets/files/03-GCP-Tools/UgandaCoffeeFinancialViability.pdf

9. Fobelets et al. (2017)

10. Fobelets et al. 2017: 5

11. https://www.nri.org/latest/news/2017/fairtrade-impacts-on-coffee-farmers-nri-s-in-depth-evaluation-published

12. Oxfam International 2002: 42

13. Durevall 2017: 1

14. Koppel and Schulze 2013 in Durevall 2017: 15

15. Jaffee 2012: 112

16. https://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-Two-million-babies-added-onto-Uganda-s-population-every-year/688334-3425848-14pynfvz/index.html

17. Van der Vossen 2005: 449

18. Van der Vossen 2005

19. https://www.climatecentral.org/gallery/graphics/heres-how-climate-change-hurts-coffee

20. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/1/eaav3473

21. https://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1476085/uganda-forest-cover-depleted-environment-minister-warns-encroachers

Sources:

Stanford Graduate School of Business 2019 accessed 01.05.2019: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/csi/defining-social-innovation

University of California, Los Angeles accessed 09.08.2019: https://www.sustain.ucla.edu/about-us/what-is-sustainability/

Mbowa, F. Nakazi, and J. Nkandu (2017): Looming Long-term Economic Effect of Climate Change on Uganda’s Coffee Industry, issue No. 96, Economic Policy Research Centre Kampala.

Borrella, C. Mataix and R. Carrasco-Gallego (2015): Smallholder Farmers in the Speciality Coffee Industry: Opportunities, Constraints and the Businesses that are Making it Possible. IDS Bulletin Volume 46 © 2015 The Authors. IDS Bulletin © 2015 Institute of Development Studies

Durevall D. (2017): Who Benefits from Fairtrade? Evidence from the Swedish Coffee Market. HUI Research and Department of Economics, University of Gothenburg

Chiputwa, B., Spielman, D. and Qaim, M. (2015). Food Standards, Certification, and Poverty among Coffee Farmers in Uganda.

Koppel and Schulze (2013) in Durevall D. (2017): Who Benefits from Fairtrade? Evidence from the Swedish Coffee Market. HUI Research and Department of Economics, University of Gothenburg.

Oxfam International (2002): Mugged, Poverty in your Coffee Mug.

Jaffee, D. (2012). Weak coffee: Certification and co-optation in the fair trade movement. Social Problems, 59(1), 94–116.

Fobelets, Rusman, Groot Ruiz (2017): Assessing Coffee Farmer Household Income. A study by True Price, Commissioned by Fairtrade International.

Steven Topik 2004: The World Coffee Market in the Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries, from Colonial To National Regimes Working Paper No. 04/04 © Steven Topik Department of History, University of California, Irvine.